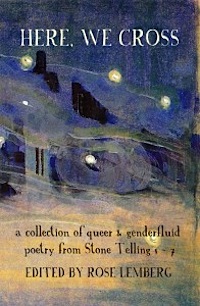

Released at WisCon 36, Rose Lemberg’s short collection of speculative poetry Here, We Cross gathers poems that deal with issues of gender, sexuality, and identity from the seven current issues of Stone Telling Magazine. Readers familiar with “Queering SFF” will note that I have previously reviewed the queer-themed seventh issue—”Bridging”—for Poetry Month, and this recently-released collection contains those stellar poems as well as several more from across the history of the magazine. As Lemberg’s introduction notes, here you “will find poems with speakers or protagonists who are lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans*, asexual, and neutrois; speakers who struggle with the body and the society’s imposed readings of that body” (iv). This collection is concerned not only with sexuality but also with gender, and with the intersections and divergences of those two axes of identity.

Released at WisCon 36, Rose Lemberg’s short collection of speculative poetry Here, We Cross gathers poems that deal with issues of gender, sexuality, and identity from the seven current issues of Stone Telling Magazine. Readers familiar with “Queering SFF” will note that I have previously reviewed the queer-themed seventh issue—”Bridging”—for Poetry Month, and this recently-released collection contains those stellar poems as well as several more from across the history of the magazine. As Lemberg’s introduction notes, here you “will find poems with speakers or protagonists who are lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans*, asexual, and neutrois; speakers who struggle with the body and the society’s imposed readings of that body” (iv). This collection is concerned not only with sexuality but also with gender, and with the intersections and divergences of those two axes of identity.

Some of the significance of the book rests in its existence as a text to be held in the hand, passed around, browsed through in shops, and enshrined on shelves; Here, We Cross is a delightful physical object. As the first release of a new mirco-press that has developed out of an existing magazine—Stone Bird Press, run by Lemberg with Jennifer Smith heading design—this book has a sort of duality: it’s symbolic of the growing presence of queer voices in the speculative poetry movement, as well as the importance of speaking into silence and having the words to communicate our selves.

Plus, aside from the symbolic weight of the physical object, it’s also a book full of great queer—and genderfluid!—poetry.

The three poems that I discussed in the previous review—”The Handcrafted Motions of Flight” by Bogi Takács, “The Clock House” by Sonya Taaffe, and “we come together we fall apart” by Lisa M. Bradley—are all reproduced here, alongside 19 other pieces that I haven’t had the chance to talk about, many of which are equally strange, fantastical, and powerful. (One additional note, to what I’ve said before: Bradley’s poem is, somehow, even more impressive in print. I hadn’t truly appreciated how long it was on my initial reading, because the narrative flow of the poem keeps the reader moving at a quick clip, but it’s quite a piece—25 pages in length, dipping and sliding from character to character to weave a multifaceted story of self and other.)

“Hair” by Hel Gurney is a poem that struck me intimately on first reading, and on the second time around, it’s still a powerful piece. The mediation of identity via this one clear visible thing—hair—is often present in queer and gender-oriented discourse, but the emotion behind the decisions we make with our hair tends to be elided from the more theoretical conversations. Gurney grasps that emotional significance and pulls it to the surface, exploring the ways of identifying self-via-hair. The poem is deeply concerned with the conflicted balance between one’s own ideas of a beautiful self with one’s gender and sexual identities, and with how society mediates those identities visually. This conflict…

The promised lands of Butch and Passing lie beyond a gate

around which these tresses twine

a lock, or two,

that lets me only look at the recognisably masculine.” (17)

…is ultimately imposed by societal insistence on conformity even in how we may be Other, which the speaker refuses at the end.

While “The Handcrafted Motions of Flight” is one great neutrois poem in this book, there are others that deal with gender identities off the binary, too. In particular, “Tertiary” by Mary Alexandra Agner deals with casting off dualistic gender-identities entirely to embrace something else, a third possibility—hence the title of the poem. The public nature of the character’s decision to remove their breasts, that symbol of womanhood, and the outcry they endure because of it make this a poem with a harsh emotional core. It is about pushing through to claim a sense of being against the odds and against hatred, but it’s also about suffering. The speaker says:

No role model for tertiary.

Thesis. Antithesis. Epiphany.

[ ]

Every un-mother in a mother’s body

hears this call. Tradition

puts its nails to chalkboard.

Out-sing the screech:

my body is my body is my body” (20).

To become a neutral third option, “alone, an end” (19), neither man nor woman, is the only option, but it isn’t easy to become a role model. It is, however, necessary to survive.

“Asteres Planetai” by Amal El-Mohtar also deals with self-definition against bigotry and repression—in this case, fighting the socially-enforced dualism of straight-or-lesbian. The poem uses the metaphor of being a roving star that shines in either night or day, but then finally also at “dusk and dawn and twi and gloam” (26). That driving metaphor perfectly illustrates the struggle, the pain, and the release of defining oneself and redefining oneself against outside influence—and this is the core of what poetry does, in many cases. It allows stories to be told via metaphor, simile, image and form that are too painful or powerful for explicit speech. (This is also why, in a Pride Month Extravaganza, including poetry seemed imperative: these are the stories that keep us awake at night, and let us know we are not alone.) El-Mohtar’s stunning imagery, and the extended metaphor of the poem, strike to the heart of an often-silenced part of queer and/or bisexual experience.

Another poem about not fitting tightly-bound boxes of identity is “The Changeling’s Lament” by Shira Lipkin. This piece, too, works on an extended metaphor—in this case, of a changeling made to fit into the human mold—to explore issues of gender and the rigidly enforced strictures of “girl.” It’s also one of the more tragic pieces of the book, whereas the majority of the poems end with an uplifting note. The changeling does not escape the strictures that have bound and hobbled them into “her” and into “girl,” but instead informs us of the struggle and the agony—takes us along on the titular lament. The final stanza is like a blow:

I am something larger,

more fluid,

less constrained.

But I am stranded in this place.

I have had to learn how to live here.

I have tried.

So hard.” (10)

Lastly, but not least, “Inner Workings” by Nancy Sheng was one of the pieces that struck me on both first and second reading. The image of the Mechanical Turk taking itself apart to find itself inside, both “king” and “queen” (“And I will touch the shape of my breasts, my hips, / before trailing my finger to the mustache above my lips.” [5]) is particularly evocative. “They would alter my stories,” (5) the Turk says, but refuses to allow themselves to be defined by the curious eyes and inquisition of others. The chess-game and the dance as forms of play and survival for the speaker add a level of realism to an otherwise fantastical piece—sometimes, that is what it takes to have the energy to define oneself: a game, a dance.

As a whole, I find Here, We Cross to be a vital book—thriving and full of life, putting to words intense emotion as well as the internal workings of identity and self. The focus on genderqueer and genderfluid poetry is a particular joy for me as a reader; these are voices still underrepresented in the larger literary conversation, but in this book they are a force, a majority, that must be considered and acknowledged. There’s also a real pleasure to be had in reading a book, cover-to-cover, that is filled with explicitly queer, trans*, neutrois, and asexual voices, all telling pieces of their stories and bringing to vivid life what it means to be them—and therefore, what it means for them to be, what steps must be taken to forge and protect a sense of identity.

As I’ve said before, Lemberg has created a necessary venue with Stone Telling Magazine—necessary for its diversity, its focus on gender and sexuality, and its encouragement of previously silenced voices. Here, We Cross is not only a selection of some of those voices put to print: it’s an engaging, provocative, ambitious collection of queer and genderfluid speculative poetry that I would recommend for any reader who’s hungry for more QUILTBAG narratives. It’s a celebration—pretty apt for Pride Month.

Lee Mandelo is a writer, critic, and editor whose primary fields of interest are speculative fiction and queer literature, especially when the two coincide. Also, comics. She can be found on Twitter or her website.

Thank you for your kind words! I’ve just received my contributor copy myself and it was a great read.

@prezzey

Yes, it’s a great book – I enjoyed it.